The Day the Laughter Died: On Losing Steve Brody

I was boarding a plane Friday when I got the devastating news that one of my closest friends, a buddy I’d known since childhood, had taken his life.

The message to “Call. It’s important” had hit my phone during the previous flight, and I knew by the tone of the childhood buddy who’d left it that the news wasn’t good.

Then came the call from a second friend, another of the “Stand By Me” group of boys who’d played baseball, rode bikes, gotten into mischief, and were generally ignorant of the privilege we lived growing up in the San Fernando Valley in the 1980s.

Despite increasing success and hordes of friends and admirers, Steve Brody, aka BrodyStevens, aka Bro, had cut short his life, leaving the rest of us the rest of our lives to wonder why and if we could’ve stopped him.

Whatever drove Steve Brody to end it all, it wasn’t fear. Bro on the pitcher’s mound was just as fearless in the face of a cocky batter digging in as he was years later in the face of Comedy Store audiences who doubted he could make them laugh.

He defied both with an ease that would’ve made the rest of us jealous if Bro hadn’t been such a stand up guy. He was also a profoundly kind human being, albeit a brilliant, zany and unpredictable one.

A few quick bits about Bro. He was the first person I know to wear compression shorts 24/7 (“for comfort”). He was insecure and perpetually mocked his appearance (“I did some modeling…in Pakistan”), and he was relentlessly upbeat for everyone but himself, lighting up dugouts, locker rooms and stages everywhere with his “Positive Push” and Brody slogans like “Enjoy it!”

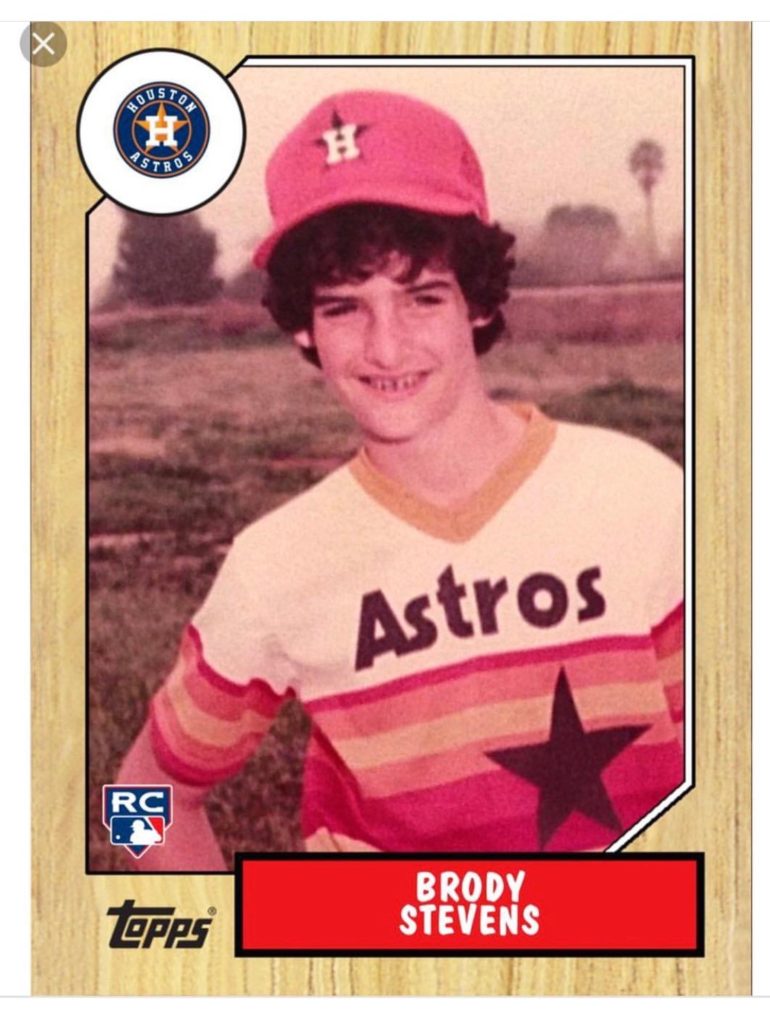

When we were 10, Bro was a giant among boys. He towered over us at 5’ 10” tall, with a bushy Jewfro that added to his stature. And he could hurl 85 mph fastballs that felt more like 100 mph from the 40-foot mound at Tarzana Little League, a rare nexus of good kids, great coaches, and everything baseball should be.

Brody, Mike Borzello, who left the phone message, Jon Bookatz, who delivered the grim news, and a handful of others became some of my closest friends during that time and remain so today.

When Joe Torre opened a baseball camp in Tarzana, Mike’s dad Matt ran it, and the four of us were counselors. Matt became something of a surrogate father to Bro, whose own father wasn’t around.

Through high school, we played together, though Brody, who lived on the dividing line for Reseda, ended up going there while Borzello and I went to Taft. Same league, different teams.

At Reseda, Brody’s size and throwing speed got him a lot of attention from major league scouts and premier Division I programs like Jim Brock’s Arizona State Sun Devils where he ended up.

He could mow down most batters, but somehow, a scrappy little hitter like me always got the better of Bro. Ego wants me to believe that I was dialed into the zone facing a friend, but it’s likely I didn’t get his best stuff. Bro never was good at saying no, and he always wanted to please.

In our 20s, the three Valley boys ended up in NYC at the same time. I took a job with a NY law firm, and Borzie was the bullpen catcher for the Yankees. Bro was starting his career in stand up and scraping to get by, living in seedy Brooklyn long before it became the hip Brooklyn of today.

In our 20s, the three Valley boys ended up in NYC at the same time. I took a job with a NY law firm, and Borzie was the bullpen catcher for the Yankees. Bro was starting his career in stand up and scraping to get by, living in seedy Brooklyn long before it became the hip Brooklyn of today.

It was a different time in many ways. My teenage daughter will find this hard to comprehend, but pre-cell phones and internet, we would often just “go out” and roam, subjecting ourselves to life’s randomness.

My second night in New York was one of those NY ‘random’ stories that would seem few and far between but were all too frequent back then.

I was getting dressed to go see Bro, who was performing at a small coffeehouse open mic in the East Village, when my new neighbor, a guy I hadn’t met, banged on my door then barged into my tiny fourth-floor walkup. Think Kramer from Seinfeld.

He pointed across the street to a pair of windows and announced the times (8:13 and 9:40) when I might see the girls who live there stepping out of their nightly showers.

I did my best to usher him to the door, but not before he talked me into a favor, a sort of quid pro quo for the voyeuristic tip. His new girlfriend had a friend from the Dominican Republic in town for the weekend. He begged me to be his wingman for the night.

He wore me down with claims that she was a model and that we’d all go to see Brody’s open mic and for drinks after. I was still trying to politely decline, when he summoned her into the room, 5’10 and gorgeous. I reluctantly agreed to take one for the team.

That night, Brody was controversial and manic, hilariously taunting everyone in the crowd including my “date.” Despite my subtle but intense head shaking imploring Brody to move on, he eventually arrived and asked, “Let’s hear about Kimelman’s girlfriend, what do you do?”

“‘I’m an English teacher,” she says in a heavy, hard to understand accent. I know immediately he’s changed the course of my night, and not for the better, when he follows with “Wait, English teacher??” Bro confirms confusedly not knowing she lives in Santo Domingo. I’m prepared for the worst with the layup she’s handed him but he’s actually quite kind and turns it on himself, letting the audience know he was never quite the student (2.5 GPA at Arizona State, not exactly an academic powerhouse), as he enunciates in perfect English, ‘You teaching me English….Ok. I wish that was a class I enrolled in at ASU…I feel like that’s a class I might have gotten my first ‘A’ in.” It’s gentle by all standards and on point. The audience laughs and I’m biting my lip to keep from crying, but it doesn’t save the night.

My neighbor and brief friend gives me a stunned look of disbelief as she and her friend storm off. Needless to say, the night didn’t quite go as planned and Bro and I had a good laugh about it years later.

At the time, my then girlfriend, soon to be wife, soon to be ex-wife, was a producer for the Food Network. Marc Maron had just done a bit or two and they were looking for more comedians willing to work similar, “man on the street” type bits into their programming.

I begged her to submit a tape that I helped Brody make and maybe get him an audition. To her credit, she walked it into the Creative Head, but he cut it short and called it “literally the worst piece of shit thing he’d ever seen.”

That was Bro. You either loved his material, or you hated it. But even if you hated it, when Brody was live he could improv off that hostility and disparage himself until you loved him — if you gave him enough time. A pre-recorded five-minute splice wasn’t the right medium for a genius like Bro.

Most people before they became famous would want you to burn an early tape like that, not Bro. Had he remembered it existed, he probably would’ve live streamed it on Periscope by now, except it was destroyed when my basement flooded years later. Today, I would give a lot to have that tape.

Brody was closest with Jon Bookatz and Mike Borzello, whose family treated him like a son. Jon and Mike are otherworldly, professionally funny, too. They just chose other careers. I’m a pretty funny fucker in my own right. Writing, as I have, about my own massive public humiliation and failure, divorce, career implosion and prison wasn’t easy, but as anyone who’s read my first book knows, I pulled it off and somehow imbued the pain with equal parts tears and laughter.

So when the four of us went out on the town and ended the night at Katz’s or Cantor’s or wherever, the caliber of table talk was as acerbic and insightful as it was uniquely hilarious.

I sensed this comic resonance among our group growing up, but I didn’t truly appreciate it until I saw what often passes for conversation. I wish we’d taped some of our high school exchanges, the conversations later in life, at Spring Training, or the Comedy Store as Bro was about to go on, but I nonetheless count those times as highpoints of my life.

I sensed this comic resonance among our group growing up, but I didn’t truly appreciate it until I saw what often passes for conversation. I wish we’d taped some of our high school exchanges, the conversations later in life, at Spring Training, or the Comedy Store as Bro was about to go on, but I nonetheless count those times as highpoints of my life.

I saw Brody perform less and less as he became more and more famous. Geography separated us by 3000 miles, and as my age and life changed, I started waking up in the morning probably around the time Brody was going to sleep after one of his Comedy Store midnight shows.

Heaven to me was being in bed asleep by 10 p.m., not watching somebody start their act after midnight, but I still managed to catch a few acts here and there when I would visit LA. Joe Rogan, Jeff Garlin, Dane Cook, Jeff Ross. Hanging out with those guys and Brody backstage was a dream for an amateur funnyman like me. I never take anything too seriously and put humor near the top of my friendship prerequisites. Naturally, Brody was one of my favorite people.

But a small part of me was always a little jealous of Bro. He was one of only a handful of my friends who did what they loved most. Baseball and comedy were the two loves of Brody’s life, and he managed to create a career and life that centered around both. He was a world-class comic and a strange mix of athletic performance artist and motivational speaker, a dugout jester who gave ballplayers a “positive push,” and they loved him for it.

Their faces lit up when Brody walked on the field or into the locker room. And that’s the big mystery. How can a guy who brings joy and laughter to everyone around him be in so much pain himself at the same time?

But it was a recurring theme for Brody. The first time I got a call from Borzello about Brody’s mental health battles was in 2011. I was headed to prison myself, and Mike called to tell me Brody had been involuntarily committed to the UCLA psych ward. “It’s been a tough year for the 818,” Mike glumly noted. We all repped 818, the San Fernando Valley’s area code, but no one as publicly and originally as Bro.

It was sometimes hard to draw the line between Brody’s craft and his real personality. Manic, brilliant, confrontational, strange. Some art is tortured, and Brody’s was no different.

He was eventually released from the psych ward, and as only Bro could do, he turned it into the basis for a biopic series he co-produced with Zach Galifianakis. The first episode is brilliant, a perfect insider view of comedy, LA, pain, striving and comebacks — all told through the brutally honest lens of Brody and his comedian pals.

The last time I saw Brody in person was two months ago over Thanksgiving. Borzello, Brody, and I grabbed lunch at Mort’s Deli and caught up on each other’s lives, Brody’s pay per view special, Cubs Baseball, politics, life, the kind of talk that flows easily after four decades together. We laughed about the all-in-one barber shop-tattoo parlor (“only in LA”), and Brody agreed to be the first guest on my upcoming podcast. I was excited because long-form conversation with Bro was always uncommon, rollicking, and insightful. His many appearances on Rogan and other podcasts are a testament to his off the cuff conversational ability and were download mainstays on my phone for long flights and walks.

Brody’s whole act was embracing failure and showing why it was temporary. He thrived on the hostile audience, the doubters and naysayers. Hell, half the time he created the hostility, but by the end of his set, he had the haters cheering for him. That was Brody. That’s another reason this hurts so much. Because it’s permanent. There’s no turning this one around.

Before I heard the news about Bro, I did something I haven’t done in a long time. I was on a flight from Baltimore to Atlanta and spent the whole flight talking to the person next to me. Like everyone else, I’m too quick to put in my airpods or headphones and retreat these days rather than engage. It was nice to meet someone new and hear their perspective and life story.

And that brings me to the failure to engage that I’ll wonder about for the rest of my life. I was exhausted from travel, chasing good weather to get to a business meeting in Baltimore and posting on the fly, promoting on Facebook a podcast I’d done.

I’m not on FB much anymore, and Brody hadn’t been either, but I noticed four successive posts from seemingly unrelated events. I’d been up for 18 hours and two flights, so it registered but not enough to do anything. Not enough to text or to comment. It’s filed away in my brain until the weekend when I have “more time.”

But it turns out there wasn’t more time, not with Brody anyway. It doesn’t matter that I wasn’t ready for the memories to stop. They stopped anyway. I spent the first night in a world without my friend alternating between numbness and tears, trying to hit rewind. But it changed nothing.

If Brody couldn’t reach out to Mike, he couldn’t reach out to anyone. I try to post about mental health once or twice a year. I’ve got friends who are better at it, more regular. But does anyone really reach out? Maybe not nearly as often as we’d like to think, so maybe we need to be like a relief pitcher, always there, always ready even if you don’t get the call, proactively asking people in our lives how they are.

As for the strangers, we meet in a time when hostility is the norm from all sides, it’s important to remember that we’re all human beings, all trying to get by, all suffering to some degree.

As well as I knew and loved Brody, I didn’t know him well enough to predict he would take his life. And maybe that’s the point. We often think we know what’s going on in other people’s lives, what’s going on in their heads. But we don’t. We can’t. So maybe we all just need to be a little bit more like Brody and opt for kindness and a smile over the cheap win, like he did on dozens of nights throughout our lives. That was Brody offstage, every day of his life. In pain himself, but still trying to make you smile.

As well as I knew and loved Brody, I didn’t know him well enough to predict he would take his life. And maybe that’s the point. We often think we know what’s going on in other people’s lives, what’s going on in their heads. But we don’t. We can’t. So maybe we all just need to be a little bit more like Brody and opt for kindness and a smile over the cheap win, like he did on dozens of nights throughout our lives. That was Brody offstage, every day of his life. In pain himself, but still trying to make you smile.

I think about that conversation on the plane before I got the news about Brody, and I’m glad it happened. Meeting new people is great, connecting with someone, hearing a new perspective. But then there are a few we all hopefully have, friends who have survived the ravages of time, geography, fights, anger, disappointment, and frustration.

Time erodes nearly everything, but not that kind of friendship. That was Brody too, a brother I shared 40 years of experiences with, someone who didn’t need small talk to break the ice but already had our history running in the background. For those kinds of friendships, that shared history has set the table, and all we have to do is enjoy the meal. For our small group of friends who’ve stayed close since childhood, that dinner table is going to have an empty seat we’ll never be able to fill. Gonna miss you Bro.